Build a Second Brain to Conquer Information Overload

Build a second brain sounds catchy, but what does it actually mean? It means means freeing up our short term and long term memory by creating a system to capture meaningful information in a way that allows our future selves to easily retrieve and work with it. Decades ago, we got away with a filing cabinet or two. Nowadays we need something considerably more robust.

We are all suffering from information overload. We are bombarded by ever increasing amounts of data and information from an ever widening array of sources, all competing for our time and attention.

For example, ten years ago the only way clients could reach out to me was email me or call me. Nowadays I have to check LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, my messages, my phone, and my email accounts plus a few other things I’m probably forgetting. I’ve noticed my clients are juggling more, finding it harder to schedule shoots, make decisions, and pick up their orders compared to 12 years ago. Multiply this across every area of your life and it can feel like trying to manage a flash flood.

Part of managing this flood of information is setting better boundaries — diverting some of the information so that it bypasses us. For example, I wrote about quitting Facebook here and what to do when you have more interests than time here. This barely scratches the surface of boundary setting, but it does illustrate how small boundaries and mindset shifts here and there can have an impact.

Another part of managing the flood is taking the time to sift through and store information in a meaningful way so that you can easily retrieve and use it, and releasing the rest of it knowing you’ve captured what matters. This concept is popularly known as a personal knowledge management system.

Tiago Forte calls this building a second brain, and he has created a detailed template and a comprehensive course to expand upon his ideas and teach his well regarded system to others.

Why Build a Second Brain?

Reason 1: Free up cognitive bandwidth and reduce stress by capturing what’s valuable and important.

If you build a second brain, you relieve the pressure on your mind to keep track of things. Much of the information that comes your way has value now or might have some value in the present. Having an automatic, logical system for storing this information gives you peace of mind that you can come back and review the information later.

Dave Allen, the author of “Getting Things Done” says that the #1 step for reducing stress and increasing productivity is to capture everything in a trusted external system because “your head’s a crappy office”.

Reason 2: Reduce time spent looking for stuff.

According to one study by McKinsey, the average employee spends over 9 hours a week searching for and gathering information. And other studies posit that we spend 6.5 months over the course of our lives looking for things in our home. This is valuable time you could be spending processing the information to create a product or communicate ideas, etc…

Reason 3: Increase productivity.

Creating and using simple systems to organize information will free up valuable time to actually process the information. Imagine that you spend 15 minutes looking for a folder with articles you’ve saved to read and write a blog post about. You feel yourself getting more frustrated as the minutes pass. When you finally find it and sit down, your equilibrium is gone, you feel irritated and annoyed. This is hardly conducive to creativity and writing!

Compare that scenario to the one where you built your second brain. You know exactly where the folder is, ready for you to process when you have the energy and desire to do so. You sit down to work and perhaps even feel a little energized because your PKMS is working so well for you.

How to Build a Second Brain

There are a number of ways to build a second brain, and some of them are extraordinarily complex! This article by Stan Garfield lists a number of strategies, and of course there is Tiago Forte’s class.

I am all about simplicity, especially when trying something new. Complex systems require a lot of time to learn and the complexity makes it hard for me to stick with. I prefer a basic system that I can customize and add on to so that it meets my specific needs and preferences.

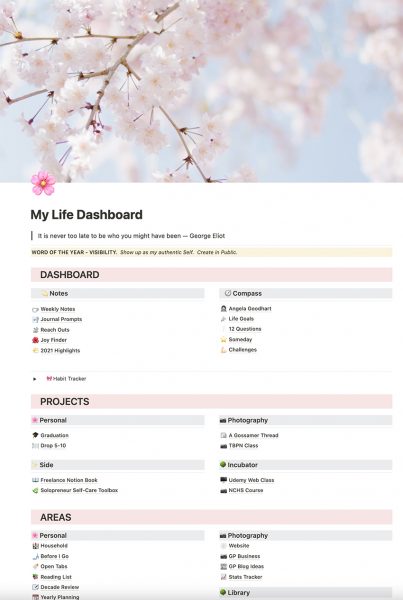

A basic personal knowledge management system (PKMS) begins with three decisions: 1. Where will your PKMS live? 2. What will your PKMS capture? and 3. How will you store information captured by your PKMS so that future you can find and use it? This fourth decision is optional. 4. How will you systematically review, process, and synthesize the information in your PKMS?

1. Location. Where will you build your second brain?

In an ideal world, there would be one location for a knowledge management system but I find this impossible. I still keep a filing cabinet for personal and business documents and receipts, and I use Notion and Evernote for my digital PKMS. Other popular alternatives include Roam Research, Obsidian, and Asana.

Something to keep in mind is how easily you can add information and content into your PKMS. For example, if I read a blog post I like, I can easily save it to Evernote or Notion. I can also import my notes from my Kindle.

Some software solutions are more like creating a library, like Evernote. Others like Obsidian and Roam Research are about connecting your notes and using the software to create content too, not just storing it.

Another consideration is cost. Roam Research has a monthly fee, Evernote and Notion both have free versions.

2. Capture. What information and data will you capture?

Every day, we are bombarded by information, people and companies vying for our attention. Not all of them actually deserve our attention. Furthermore, with so much information easily searchable on our computers or phones, it doesn’t make sense to save everything for future reference.

I capture information related to projects (tasks with deadlines), responsibilities (ongoing areas to maintain, like vacations, health, photography), and interests (like painting, block printing, and poetry). This is loosely modeled after Tiago Forte’s system of PARA, or Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives.

I let other information flow by me, knowing that if it ever becomes and interest or a responsibility or a project, I won’t have any trouble finding it again to put into my system.

3. Capture. How will you store information so it is readily accessible by future you?

This is the meat of your PKMS. All of the software solutions have search functions, and some allow you to create tags and keywords as another way to find your notes.

It makes sense, however, to have some sort of framework or structure for saving information.

In my system, I use two high level folders called projects (for my projects) and areas (for my responsibilities and interests).

Projects are related to tasks I am working on that have a deadline. I try not to have too many projects going on at one time; between 5-10. When a project is completed, I move it to the relevant area.

Areas are my responsibilities and interests. Responsibilities are areas I have to maintain, like my business bookkeeping or holiday planning. Interests are areas that I’m curious about and enjoy, like art or mindfulness.

Tiago makes a great point about how one’s to-do list should only include projects, things that have deadlines. He says your project list should change week to week to create a rhythm and momentum of completion and crossing things off of your list. He points out that having a to-do list filled with areas of responsibility is problematic because that item will ALWAYS be on your to-do list (since it’s an area with a standard that needs to be maintained) and it’s therefore demoralizing since you can never cross it off. This makes perfect sense to me — I love my to-do lists now that I only put time-bound tasks on it.

Tiago also recommends using your second brain organizational structure across all of your apps and programs because consistency will make it easier to retrieve and store information. So my projects and areas are the same in my email program, my hard drive on my computer, and in Notion.

4. Review. How will you systematically review, process, and synthesize information in your PKM?

One school of thought is that the purpose of collecting and organizing information is to create something with it, a blog article, a book, a project. Most PKMS advocates dislike the idea of hoarding and collecting information just to have it, although there are some who enjoy the idea of a digital garden of ideas that they might not necessarily act on.

This is the weak link in my system right now. I don’t have a system for reviewing information – I simply retrieve it when I need it. Different applications make review and connecting notes easier than Notion does. For example, Roam Research and Obsidian are excellent for linking the notes you create and the information you save, so if you write about mindfulness you can also see all of the other times you wrote about mindfulness too. This connecting of ideas and resources can be extremely fruitful in terms of producing output and it is something I would like to incorporate when I develop my review process.

Final Notes About Building a Second Brain

Think of your knowledge management system as a garden that needs maintenance and tending, not as a work of art that you work on until it is complete. This relieves you of the pressure to create the BEST system from the beginning. Your needs will change and grow, and the tools you prefer will evolve. It’s okay to change things up! I’m still tinkering with my Notion dashboard.

Just jump in and learn by doing! If you have any questions or comments or just want to chat about Notion or knowledge management systems, you can get in touch here.

Did you enjoy this article? You might enjoy my monthly newsletter!